I rarely venture into large retail areas and shopping centres. They make me feel unwell. I’m rather claustrophobic to begin with. I also have lupus, one of my symptoms is a quite extreme photosensitivity. The lighting in these places quite often triggers an attack of vertigo, nausea, incapacitating disorientation, co-ordination difficulties, muscle rigidity, temporary and severe visual distortions and a very severe headache.

However, I visited one recently with a friend, who was doing some last-minute Christmas shopping. He promised we would visit just two shops, and that our visit would be over quickly.

What struck me straight away is how much retail design is now just about revenue-producing. Shopping malls are unforgiving, soulless and unfriendly places. I was reminded of something I read by David Harvey, about the stark reality of shrinking, privatised and devalued public spaces. Neoliberal marketisation has manifested ongoing conflicts over public access to public space, where profiteering reigns supreme.

My experience of a shopping mall was deeply alienating and physically damaging. It brought with it a recognition of how some groups of people are being coerced and physically situated in the world – how citizens think and act is increasingly being determined by ‘choice architecture’ – which is all-pervasive: it’s situated at a political, economic, cultural, social and material level. Hostile architecture – in all of its forms – is both a historic and contemporary leitmotif of hegemony.

Architecture, in both the abstract and the concrete, has become a mechanism of asymmetrically changing citizens’ perceptions, senses, choices and behaviours – ultimately it is being used as a means of defining and targeting politically defined others, enforcing social exclusion and imposing an extremely authoritarian regime of social control.

Citizens targeted by a range of ‘choice architecture’ as a means of fulfiling a neoliberal ‘behavioural change’ agenda (aimed at fulfiling politically defined neoliberal ‘outcomes’) are those who are already profoundly disempowered and, not by coincidence, among the poorest social groups. The phrase choice architecture implies a range of offered options, with the most ‘optimal’ (defined as being in our ‘best interest’) highlighted or being ‘incentivised’ in some way. However, increasingly, choice architecture is being used to limit the choices of those who already experience heavy socioeconomic and political constraints on their available decision-making options.

The shopping mall made me ill very quickly. Within minutes the repulsive lighting triggered an attack of vertigo, nausea, co-ordination and visual difficulties. I looked for somewhere to sit, only to find that the seating was not designed for actually sitting on.

The public seating that’s just a prop.

This radically limited my choices. In order to sit down to recover sufficiently to escape the building, the only option I had was to buy a drink in a cafe, where the seating is rather more comfortable and fulfils its function. I needed to sit down in order to muster myself to head for the exit, situated at the other end of the building.

At this point it dawned on me that the hostile seating also fulfils its function. In my short visit, I had been ushered through the frightfully cold, clinical and unfriendly building, compelled to make a purchase I didn’t actually want and then pretty much rudely ejected from the building. It wasn’t a public space designed for me. Or for the heavily pregnant woman who also needed to sit for a while. It didn’t accommodate human diversity. It didn’t extend a welcome or comfort to all of its guests. The functions and comforts of the building are arranged to be steeply stratified, reflecting the conditions of our social reality. The only shred of comfort it offered me was conditional on making a purchase.

When the purpose of public seating isn’t taking the weight off your feet and providing rest.

Urbanomics and the cutting edge of social exclusion: what is ‘defensive architecture’ defending?

Social exclusion exists on multiple levels. The distribution of wealth and power, access to citizenship rights and freedoms, political influence and consideration are a few expressions of inclusion or exclusion. It also exists and operates in time and space – in places.

Our towns and cities have also increasingly become spaces that communicate to us who ‘belongs’ and who isn’t welcome. From gated communities and the rise of private policing, surveillance and security to retail spaces designed to fulfil pure profiteering over human need, our urban spaces have become extremely anticommunal; they are now places where an exclusive social-spatial order is being defined and enforced. That order reflects and contains the social-economic order.

Retail spaces are places of increasing psychological and sensual manipulation and control. Hostile architecture is designed and installed to protect the private interests of the wealthy, propertied class in upmarket residential areas and to protect the private profiteering interests of the corporate sector in retail complexes.

The very design of our contemporary cities reflects, directs and amplifies political and social prejudices, discrimination and hostility toward marginalised social groups. Hostile architectural forms prevent people from seeking refuge and comfort in public spaces. Places that once reflected human coexistence are being encroached upon, restrictions are placed on access and limits to its commercial usage, demarcating public and private property and permitting an unrestrained commodification of urban spaces and property.

In 2014, widespread public outrage arose when a luxury London apartment building installed anti-homeless spikes to prevent people from sleeping in an alcove near the front door. The spikes, which were later removed following the public outcry, drew public attention to the broader urban phenomenon of hostile architecture.

Dehumanising ‘defensive architecture’ – ranging from benches in parks and bus stations that you can’t actually sit on, to railings that look like the inside of iron maidens, to metal spikes that shriek ‘this is our private space, go away’ – is transforming urban landscapes into a brutal battleground for the haves and socioeconomically excluded have-nots. The buildings and spaces are designed to convey often subtle messages about who is welcome and who is not.

Hostile architecture is designed and installed to target, frustrate deter and ultimately exclude citizens who fall within ‘unwanted’ demographics.

Although many hostile architecture designs target homeless people, there are also a number of exclusion strategies aimed at deterring congregating young people, many of these are less physical or obvious than impossibly uncomfortable seating, which is primarily designed and installed to prevent homeless people from finding a space to sleep or rest. However, the seating also excludes others who may need to rest more frequently, from sitting comfortably – from pregnant women, nursing mothers with babies and young children to those who are ill, elderly and disabled citizens.

Some businesses play classical music as a deterrent – based on an assumption that young people don’t like it. Other sound-based strategies include the use of high-frequency sonic buzz generators (the ‘mosquito device’) meant to be audible only to young people under the age of 25.

Some housing estates in the UK have also installed pink lighting, aimed at highlighting teenage blemishes, and deterring young males, who, it is assumed, regard pink ‘calming’ light as ‘uncool’. There is little data to show how well these remarkably oppressive strategies actually work. Nor is anyone monitoring the potential harm they may cause to people’s health and wellbeing. Furthermore, no-one seems to care about the psychological impact such oppressive strategies have on the targeted demographics – the intended and unintended consequences for the sighted populations, and those who aren’t being targeted.

Blue lighting in public toilets via Unpleasant Design

Blue lighting has been used in public toilets to deter intravenous drug users; the colour allegedly makes it harder for people to locate their veins. It was claimed that public street crime declined in Glasgow, Scotland following the installation of blue street lights, but it’s difficult to attribute this effect to the new lighting. Blue may have calming effects or may simply (in contrast to yellow) create an unusual atmosphere in which people are uncomfortable – actingout or otherwise. So questions remain about causality versus correlation. Again, no-one is monitoring the potential harm that such coercive strategies may cause. Blue light is particularly dangerous for some migraine sufferers and those with immune-related illnesses, for example, and others who are sensitive to flickering light.

Hostile architecture isn’t a recent phenomenon

Charles Pierre Baudelaire wrote a lot about the transformation of Paris in the 1850s and 1860s. For example, The Eyes of the Poor captures a whole series of themes and social conflicts that accompanied the radical re-design of Paris under Georges-Eugène Haussmann‘s controversial programme of urban planning interventions.

Baron Haussmann was considered an arrogant, autocratic vandal by many, regarded as a sinister man who ripped the historic heart out of Paris, driving his boulevards through the city’s slums to help the French army crush popular uprisings. Republican opponents criticised the brutality of the work. They saw his avenues as imperialist tools to neuter fermenting civil unrest in working-class areas, allowing troops to be rapidly deployed to quell revolt. Haussmann was also accused of social engineering by destroying the economically mixed areas where rich and poor rubbed shoulders, instead creating distinct wealthy arrondissements.

Baudelaire opens the prose by asking his lover if she understands why it is that he suddenly hates her. Throughout the whole day, he says, they had shared their thoughts and feelings in the utmost intimacy, almost as if they were one. And then:

“That evening, feeling a little tired, you wanted to sit down in front of a new cafe forming the corner of a new boulevard still littered with rubbish but that already displayed proudly its unfinished splendors. The cafe was dazzling. Even the gas burned with all the ardor of a debut, and lighted with all its might the blinding whiteness of the walls, the expanse of mirrors, the gold cornices and moldings…..nymphs and goddesses bearing on their heads piles of fruits, pates and game…..all history and all mythology pandering to gluttony.

On the street directly in front of us, a worthy man of about forty, with tired face and greying beard, was standing holding a small boy by the hand and carrying on his arm another little thing, still too weak to walk. He was playing nurse-maid, taking the children for an evening stroll. They were in rags. The three faces were extraordinarily serious, and those six eyes stared fixedly at the new cafe with admiration, equal in degree but differing in kind according to their ages.

The eyes of the father said: “How beautiful it is! How beautiful it is! All the gold of the poor world must have found its way onto those walls.”

The eyes of the little boy: “How beautiful it is! How beautiful it is! But it is a house where only people who are not like us can go.”

As for the baby, he was much too fascinated to express anything but joy – utterly stupid and profound.

Song writers say that pleasure ennobles the soul and softens the heart. The song was right that evening as far as I was concerned. Not only was I touched by this family of eyes, but I was even a little ashamed of our glasses and decanters, too big for our thirst. I turned my eyes to look into yours, dear love, to read my thoughts in them; and as I plunged my eyes into your eyes, so beautiful and so curiously soft, into those green eyes, home of Caprice and governed by the Moon, you said:

“Those people are insufferable with their great saucer eyes. Can’t you tell the proprietor

to send them away?”

So you see how difficult it is to understand one another, my dear angel, how incommunicable thought is, even between two people in love.”

I like David Harvey‘s observations on this piece. He says “What is so remarkable about this prose poem is not only the way in which it depicts the contested character of public space and the inherent porosity of the boundary between the public and the private (the latter even including a lover’s thoughts provoking a lover’s quarrel), but how it generates a sense of space where ambiguities of proprietorship, of aesthetics, of social relations (class and gender in particular) and the political economy of everyday life collide.”

The parallels here are concerning the right to occupy a public space, which is contested by the author’s lover who wants someone to assert proprietorship over it and control its uses.

The cafe is not exactly a private space either; it is a space within which a selective public is allowed for commercial and consumption purposes.

There is no safe space – the unrelenting message of hostile architecture

What message do hostile architectural features send out to those they target? Young people are being intentionally excluded from their own communities, for example, leaving them with significantly fewer safe spaces to meet and socialise. At the same time, youth provision has been radically reduced under the Conservative neoliberal austerity programme – youth services were cut by at least £387m from April 2010 to 2016. I know from my own experience as a youth and community worker that there is a positive correlation between inclusive, co-designed, needs-led youth work interventions and significantly lower levels of antisocial behaviour. The message to young people from society is that they don’t belong in public spaces and communities. Young people nowadays should be neither seen nor heard.

It seems that the creation of hostile environments – operating simultaneously at a physical, behavioural, cognitive, emotional, psychological and subliminal level – is being used to replace public services – traditional support mechanisms and provisions – in order to cut public spending and pander to the neoliberal ideal of austerity and ‘rolling back the state’.

It also serves to normalise prejudice, discrimination and exclusion that is political- in its origin. Neoliberalism fosters prejudice, discrimination and it seems it is incompatible with basic humanism, human rights, inclusion and democracy.

The government are no longer investing in more appropriate, sustainable and humane responses to the social problems created by ideologically-driven decision-making, anti-public policies and subsequently arising structural inequalities – the direct result of a totalising neoliberal socioeconomic organisation.

For example, homeless people and increasingly disenfranchised and alienated young people would benefit from the traditional provision of shelters, safe spaces, support and public services. Instead both groups are being driven from the formerly safe urban enclaves they inhabited into socioeconomic wastelands and exclaves – places of exile that hide them from public visibility and place further distance between them and wider society.

Homelessness, poverty, inequality, disempowerment and alienation continue but those affected are being exiled to publicly invisible spaces so that these processes do not disturb the activities and comfort of urban consumers or offend the sensibilities of the corporate sector and property owners. After all, nothing is more important that profit. Least of all human need.

Homelessness as political, economic and public exile

Last year, when interviewed by the national homelessness charity Crisis, rough sleepers reported being brutally hosed with water by security guards to make them move on, and an increase in the use of other ‘deterrent’ measures. More than 450 people were surveyed in homelessness services across England and Wales. 6 in 10 reported an increase over the past year in ‘defensive architecture’ to keep homeless people away, making sitting or lying down impossible – including hostile spikes and railings, curved or segregated, deliberately uncomfortable benches and gated doorways.

Others said they had experienced deliberate ‘noise pollution’, such as loud music or recorded birdsong and traffic sounds, making it hard or impossible to sleep. Almost two-thirds of respondents said there had been an increase in the number of wardens and security guards in public spaces, who were regularly moving people on in the middle of the night, sometimes by washing down spaces where people were attempting to rest or sleep. Others reported noise being played over loudspeakers in tunnels and outside buildings.

Crisis chief executive Jon Sparkes said he had been shocked by the findings. He said: “It’s dehumanising people. If people have chosen the safest, driest spot they can find, your moving them along is making life more dangerous.

“The rise of hostile measures is a sad indictment of how we treat the most vulnerable in our society. Having to sleep rough is devastating enough, and we need to acknowledge that homelessness is rising and work together to end it. We should be helping people off the streets to rebuild their lives – not just hurting them or throwing water on them.”

‘Defensive architecture’ is a violent gesture and a symbol of a profound social and cultural unkindness. It is considered, calculated, designed, approved, funded and installed with the intention to dehumanise and to communicate exclusion. It reveals how a corporate oligarchy has prioritised a hardened, superficial style and profit motive over human need, diversity, complexity and inclusion.

Hostile architecture is covert in its capacity to exclude – designed so that those deemed ‘legitimate’ users of urban public space may enjoy a seemingly open, comfortable and inclusive urban environment, uninterrupted by the sight of the casualities of the same socioeconomic system that they derive benefit from. Superficially, dysfunctional benches and spikes appear as an ‘arty’ type of urban design. Visible surveillance technologies make people feel safe.

It’s not a society that everyone experiences in the same way, nor one which everyone feels comfortable and safe in, however.

Hidden from public view, dismissed from political consideration

Earlier this month, Britain’s statistics watchdog said it is considering an investigation into comments made by Theresa May following complaints that they misrepresented the extent of homelessness and misled parliament.

The UK Statistics Authority (UKSA) confirmed that concerns had been raised after the prime minister tried to claim in Parliament that ‘statutory homelessness peaked under the Labour government and is down by over 50 per cent since then.’ Official figures show that the number of households in temporary accommodation stood at 79,190 at the end of September, up 65% on the low of 48,010 in December 2010. Liberal Democrat peer Olly Grender, who made the complaint, also raised concerns last year about the government’s use of the same statistics.

Grender said: “It seems particularly worrying, as we learn today of the increase in homelessness, that this government is still using spin rather than understanding and solving the problem.”

Baroness Grender’s previous complaint prompted UKSA to rebuke the Department for Communities and Local Government. The department claimed homelessness had halved since 2003 but glossed over the fact this referred only to those who met the narrow definition of statutory homelessness, while the overall number of homeless people had not dropped.

May was accused of callousness when Labour MP Rosena Allin-Khan recently raised questions about homelessness and the rise in food bank use. The prime minister responded, saying that families who qualified as homeless had the right to be found a bed for the night. She said: “Anybody hearing that will assume that what that means is that 2,500 children will be sleeping on our streets. It does not.

“It is important that we are clear about this for all those who hear these questions because, as we all know, families with children who are accepted as homeless will be provided with accommodation.”

Finger wagging authoritarian Theresa May tells us that children in temporary accommodation are not waking up on the streets.

However, Matthew Downie, the director of policy at the Crisis charity for homeless people, said: “The issue we’ve got at the moment is that it’s just taking such a long time for people who are accepted as homeless to get into proper, stable, decent accommodation. And that’s because local councils are struggling so much to access that accommodation in the overheated, broken housing market we’ve got, and with housing benefit rates being nowhere near the market rents that they need to pay.”

He said that while May highlighted a decline in what is categorised as ‘statutory homelessness’, rough sleeping had increased by 130% since 2010.

The category of ‘statutory homelssness’ has also been redefined to include fewer people who qualify for housing support.

Last year, May surprisingly unveiled a £40 million package designed to ‘prevent’ homelessness by intervening to help individuals and families before they end up on the streets. It was claimed that the ‘shift’ in government policy will move the focus away from dealing with the consequences of homelessness and place prevention ‘at the heart’ of the government’s approach.

Writing in the Big Issue magazine – sold by homeless people – May said: “We know there is no single cause of homelessness and those at risk can often suffer from complex issues such as domestic abuse, addiction, mental health issues or redundancy.”

However, there are a few causes that the prime minister seems to have overlooked, amid the Conservative ritualistic chanting about ‘personal responsibility’ and a ‘culture of entitlement’, which always reflects assumptions and prejudices about the causal factors of social and economic problems. It’s politically expedient to blame the victims and not the perpetrators, these days. It’s also another symptom of failing neoliberal policies.

It’s a curious fact that wealthy people also experience ‘complex issues’ such as addiction, mental health problems and domestic abuse, but they don’t tend to experience homelessness and poverty as a result. The government seems to have completely overlooked the correlation between rising inequality and austerity, and increasing poverty and homelessness – which are direct consequences of political decision-making. Furthermore, a deregulated private sector has meant that rising rents have made tenancies increasingly precarious.

Last year, ludicrously, the Government backed new law to prevent people made homeless through government policy from becoming homeless. The aim is to ‘support’ people by ‘behavioural change’ policies, rather than by supporting people in material hardship – absolute poverty – who are unable to meet their basic survival needs because of the government’s regressive attitude and traditional prejudices about the causes of poverty and the impact of austerity cuts.

Welfare ‘reforms’, such as the increased and extended use of sanctions, the bedroom tax, council tax reduction, benefit caps and the cuts implemented by stealth through Universal Credit have all contributed to a significant rise in repossession actions by social landlords in a trend expected to continue to rise as arrears increase and temporary financial support shrinks.

Housing benefit cuts have played a large part in many cases of homelessness caused by landlords ending a private rental tenancy, and made it harder for those who lost their home to be rehoused.

The most recent National Audit Office (NAO) report on homelessness says, in summary:

- 88,410 homeless households applied for homelessness assistance

during 2016-17 - 105,240 households were threatened with homelessness and helped to remain in their own home by local authorities during 2016-17 (increase of 63%

since 2009-10) - 4,134 rough sleepers counted and estimated on a single night in autumn

2016 (increase of 134% since autumn 2010) - Threefold approximate increase in the number of households recorded

as homeless following the end of an assured shorthold tenancy

since 2010-11 - 21,950 households were placed in temporary accommodation outside the local

authority that recorded them as homeless at March 2017 (increase

of 248% since March 2011) - The end of an assured shorthold tenancy is the defining characteristic of the increase in homelessness that has occurred since 2010

Among the recommendations the NAO report authors make is this one: The government, led by the Department [for Housing] and the Department for Work and Pensions, should develop a much better understanding of the interactions between local housing markets and welfare reform in order to evaluate fully the causes of homelessness.

Record high numbers of families are becoming homeless after being evicted by private landlords and finding themselves unable to afford a suitable alternative place to live, government figures from last year have also shown. Not that empirical evidence seems to matter to the Government, who prefer a purely ideological approach to policy, rather than an evidence-based one.

The NAO point out that Conservative ministers have not evaluated the effect of their own welfare ‘reforms’ (a euphemism for cuts) on homelessness, nor the effect of own initiatives in this area. Although local councils are required to have a homelessness strategy, it isn’t monitored. There is no published cross-government strategy to deal with homelessness whatsoever.

Ministers have no basic understanding on the causes or costs of rising homelessness, and have shown no inclination to grasp how the problem has been fuelled in part by housing benefit cuts, the NAO says. It concludes that the government’s attempts to address homelessness since 2011 have failed to deliver value for money.

More than 4,000 people were sleeping rough in 2016, according to the report, an increase of 134% since 2010. There were 77,000 households – including 120,000 children – housed in temporary accommodation in March 2017, up from 49,000 in 2011 and costing £845m a year in housing benefit.

Homelessness has grown most sharply among households renting privately who struggle to afford to live in expensive areas such as London and the south-east, the NAO found. Private rents in the capital have risen by 24% since the start of the decade, while average earnings have increased by just 3%.

Cuts to local housing allowance (LHA) – a benefit intended to help tenants meet the cost of private rents – have also contributed to the crisis, the report says. LHA support has fallen behind rent levels in many areas, forcing tenants to cover an average rent shortfall of £50 a week in London and £26 a week elsewhere. This is at the same time that the cost of living has been rising more generally, while both in-work and out-of-work welfare support has been cut. It no longer provides sufficient safety net support to meet people’s basic needs for fuel, food and shelter.

It was assumed when welfare amounts were originally calculated that people would not be expected to pay rates/council tax and rent. However, this is no longer the case. People are now expected to use money that is allocated for food and fuel to pay a shortfall in housing support, and meet the additional costs of council tax, bedroom tax and so on.

Local authority attempts to manage the homelessness crisis have been considerably constrained by a shrinking stock of affordable council and housing association homes, coupled with a lack of affordable new properties. London councils have been reduced to offering increasingly reluctant landlords £4,000 to persuade them to offer a tenancy to homeless families on benefits.

Housing shortages in high-rent areas mean that a third of homeless households are placed in temporary housing outside of their home borough, the NAO said. This damages community and family ties, disrupts support networks, isolates families and disrupts children and you people’s education.

London councils are buying up homes in cheaper boroughs outside of the capital to house homeless families, in turn exacerbating the housing crisis in those areas.

Polly Neate, the chief executive of the housing charity Shelter, said: “The NAO has found what Shelter sees every day, that for many families our housing market is a daily nightmare of rising costs and falling benefits which is leading to nothing less than a national crisis.”

Matt Downie, the director of policy and external affairs at Crisis, said: “The NAO demonstrates that while some parts of government are actively driving the problem, other parts are left to pick up the pieces, causing misery for thousands more people as they slip into homelessness.”

Meg Hillier MP, the chair of the Commons public accounts committee, said the NAO had highlighted a ‘national scandal’. “This reports illustrates the very real human cost of the government’s failure to ensure people have access to affordable housing,” she added.

More than 9,000 people are sleeping rough on the streets and more than 78,000 households, including 120,000 children, are homeless and living in temporary accommodation, often of a poor standard, according to the Commons public accounts committee.

The Committee say in a report that the attitude of the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) to reducing homelessness has been ‘unacceptably complacent’.

John Healey, the shadow housing secretary, said: “This damning cross-party report shows that the Conservatives have caused the crisis of rapidly rising homelessness but have no plan to fix it.

“This Christmas the increase in homelessness is visible in almost every town and city in the country, but today’s report confirms ministers lack both an understanding of the problem and any urgency in finding solutions.

“After an unprecedented decline in homelessness under Labour, Conservative policy decisions are directly responsible for rising homelessness. You can’t help the homeless without the homes, and ministers have driven new social rented homes to the lowest level on record.”

Surely it’s a reasonable and fundamental expectation of citizens that a government in a democratic, civilised and wealthy society ensures that the population can meet their basic survival needs.

The fact that absolute poverty and destitution exist in a wealthy, developed and democratic nation is shamefully offensive. However, Conservatives tend to be outraged by poor people themselves, rather than by their own political choices and the design of socioeconomic processes that created inequality and poverty. The government’s response to the adverse consequences of neoliberalism is increasingly despotic and authoritarian.

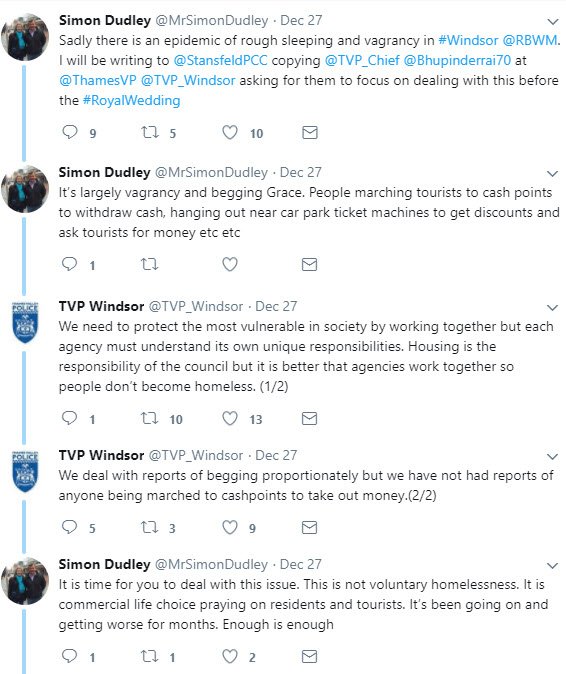

The comments below from Simon Dudley, the Conservative Leader of the Maidenhead Riverside Council and ironically, a director of a Government agency that supports house building, (Homes and Community Agency (HCA)) reflect a fairly standardised, authoritarian, dehumanising Conservative attitude towards homelessness.

Note the stigmatising language use – likening homelessness and poverty to disease – an epidemic. Dudley’s underpinning prejudice is very evident in the comment that homelessness is a commercial lifestyle choice, and the demand that the police ‘deal’ with it highlights his knee-jerk authoritarian response:

Dudley uses the word ‘vagrancy’, which implies that it is the condition and characteristics of homeless people who causes homelessness, rather than social, political and economic conditions, such as inequality, low wages, austerity and punitive welfare policies. The first major vagrancy law was passed in 1349 to increase the national workforce and impose social control following the Black Death, by making ‘idleness’ (unemployment) and moving to other areas for higher wages an offence. The establishment has a long tradition of punishing those who are, for whatever reason, economically ‘inactive’: who aren’t contributing to the private wealth accumulation of others.

The Vagrancy Act of 1824 is an Act of Parliament that made it an offence to sleep rough or beg. Anyone in England and Wales found to be homeless or begging subsistence money can be arrested. Though amended several times, certain sections of the original 1824 Vagrancy Act remain in force in England and Wales. It’s main aim was removing undesirables from public view. The act assumed that homelessness was due to idleness and therefore deliberate, and made it a criminal offence to engage in behaviours associated with extreme poverty.

The language that Dudley uses speaks volumes about his prejudiced and regressive view of homelessness and poverty. And his scorn for democracy.

The 1977 Housing (Homeless Persons) Act restricted the homeless housing requirements so that only individuals who were affected by natural disasters could receive housing accommodation from the local authorities. This was partly due to well-organised opposition from district councils and Conservative MPs, who managed to amend

the Bill considerably in its passage through Parliament, resulting in the rejection of many homeless applications received by the local government because of strict qualifying criteria.

For the first time, the 1977 Act gave local authorities the legal duty to house homeless people in ‘priority’ need, and to provide advice and assistance to those who did not qualify as having a priority need. However, the Act also made it difficult for homeless individuals without children to receive accommodations provided by local authorities, by reducing the categories and definitions of ‘priority need’.

Use of the law that criminalises homeless people may generally include:

- Restricting the public areas in which sitting or sleeping are allowed.

- Removing the homeless from particular areas.

- Prohibiting begging.

- Selective enforcement of laws.

Murphy James, manager of the Windsor Homeless Project, branded Cllr Dudley’s comments ‘disgusting’ and described the Southall accommodation offered by the Royal Borough of Windsor & Maidenhead as ‘rat infested’.

He said: “It shows he hasn’t got a clue. He has quite obviously never walked even an inch in their shoes.

“It is absolutely disgusting he is putting out such an opinion that it is a commercial life choice.”

James added the royal wedding should not be the only reason for helping people on the streets.

“I am a royalist but it should have zero to do with the royal wedding,” he said.

“Nobody in this country should be on the streets.”

Dudley should pay more attention to national trends instead of attempting to blame homeless people for the consequences of government policies, as many in work are also experiencing destitution.

This short film challenges the stereoytypes that Dudley presents. This is 21st century Britain. But still there are people without homes, still people living rough on the streets, including some who are in work, even some doing vital jobs in the public sector, low paid and increasingly struggling to keep a roof over their heads. Central government doesn’t keep statistics on the ‘working homeless’. But we do know that overall the number of homeless people is once again on the rise.

Meanwhile, figures obtained via a Freedom of Information request by the Liberal Democrats from 234 councils show almost 45,000 people aged 18-24 have come forward in past year for help with homelessness. With more than 100 local authorities not providing information, the real statistic could well be above 70,000.

As Polly Toynbee says: “Food banks and rough sleeping are now the public face of this Tory era, that will end as changing public attitudes show rising concern at so much deliberately induced destitution.”

While the inglorious powers that be spout meaningless, incoherent and reactionary authoritarian bile, citizens are dying as a direct consequence of meaningless, incoherent and reactionary Conservative policies.

I don’t make any money from my work. I am disabled because of illness and have a very limited income. But you can help by making a donation to help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.

Reblogged this on disabledsingleparent.

LikeLike

Tweeted @melissacade68

LikeLike

It is an excellent and very ‘moving’ report Ms Jones as are all your reports and observations. I greatly admire all that you have done and all that you do in the cause of that which I see as ‘enlightenment’.

The big question for me remains – how does one penetrate that very narrow ‘tory’ mindset and effect any sort of meaningful change??? All good wishes for the New Year and thank you for all you do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Pat. I doubt very much that we can penetrate the narrow Tory mindset. Occasionally, there is a visible conflict and arising challenges within the Conservative movement though, which is promising. For example, Conservative MPs such as Anna Soubry and Heidi Allen and others voted against their own party recently, voting with the opposition and ensuring that elements of Brexit legislation are debated democratically in parliament.

My aim is to persuade public, charity, academic, professional and grassroots campaigners that meaningful change is essential. As well as pushing for progressive change, the Tories will necessarily need to be removed from office, since they have shown over the past 7 years that they don’t care about the dire impacts and social damage caused by their draconian policies, that they don’t value human rights and democracy, that they don’t respond to reasoned debate and rationality, or empirical evidence. They will never listen to anyone who challenges their fundamentalism and neoliberal ideology. That makes them unfit for office. Next General Election, they will (and must) be voted out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

brilliant , great artical as ever, we at greater manchester housing action often try and raise awareness of architecture as power and control rather than building for people. wed love you to get in touch via me or our facebook and chat about this. your very much in our groove. chat soon. debi GMHA

LikeLiked by 1 person

Will do Debi

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Fear and loathing in Great Britain.

LikeLike

What’s up, I want to subscribe for this webpage to take most up-to-date updates, thus where

can i do it please help.

LikeLike

In the drop down menu at the top of the page

LikeLike

That describes what I’ve noticed about public spaces very well. While I don’t have the sensitivity that you do, it seems the lighting and general environment of shopping malls and large stores is designed to cause a sense of confusion and disorientation, to encourage people to think less rationally and spend more. And the shopping malls almost always contain the same bland range of chain stores – no interesting small businesses or second-hand shops, for example. As shopping malls are private property, the owners can impose their own rules which go beyond the laws, and more easily exclude and discourage certain people.

At my local bus station, the “seats” are angled bars about four inches deep – inconveniencing everyone who uses them. Even in this small market town, there are some other examples of hostile architecture.

A while ago, dim UV lighting was installed over the cubicles in some of the public toilets, once again inconveniencing every user. I seriously considered changing the fluorescent tubes myself (since then one of them has been replaced by a normal white one – I don’t know who did it).

All these things give the impression of government and local authorities being against the general public, not for us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. The video about Lindy made me cry.

LikeLiked by 1 person