The Institute For Government (IFG) published their annual Whitehall Monitor Report on Thursday, presenting an insight and analysis of the size, shape and performance of government and the civil service.

In the opening paragraph, the IFG say: “The Prime Minister Theresa May lost her parliamentary majority in a snap general election. Revelations about ministers’ inappropriate conduct resulted in three Cabinet resignations. Preparations for Brexit have been disrupted by the snap election, by turnover in personnel and by difficulties in parliamentary management. The Government faces challenges in key public services, notably hospitals, prisons and adult social care.

It was noted in the report that preparations for Brexit have been disrupted by “difficulties in parliamentary management”. The Government has introduced only five of the nine new bills it says are needed for Brexit, and a third of the Government’s major projects worth over £1bn are at risk of not being delivered on time and on budget.

This Whitehall Monitor annual report – which is the fifth – summarises:

- The political situation following the early election constrained the Prime Minister’s political authority and created challenges for the Government’s legislative programme and management of public services, major projects and Brexit.

- The civil service is growing, in terms of size, but should be more diverse.

- Government is less open than it was after 2010, and is not using data as effectively as it should.

I’ve used the summary to shape my analysis.

Fiscal management

The forecasts for tax revenues have been downgraded, the Government also forgoes billions of pounds through tax expenditures that are not subject to rigorous value-for-money assessments.

Since 2010, the value of liabilities on the government’s balance sheet has grown more quickly than the value of assets, increasing net liabilities. Furthermore, “revenue is not likely to overtake spending, in the foreseeable future”.

Despite the promises from George Osborne of a budget surplus by 2020, and his fiscal straitjacket – the imposed, rigid programme of spending cuts and austerity for the majority of citizens, and tax cuts to the wealthiest ones.

In real terms, revenues from taxes have grown 7% since 2010/11. This is largely the result of:

- VAT receipts increasing by 22% (partly due to the standard VAT rate increasing from 17.5% to 20% in 2011)

- National Insurance contributions increasing by 11%

- Some increases in income tax collected following a stabilisation following the global crash

Council tax is also included in Treasury revenue, and that will have risen, since many low paid or out of work people now pay a contribution, whereas previously, they were exempt. Despite the increases in VAT, revenue from the sale of goods and services has fallen 34% since 2010/11.

For the 2017 Autumn Budget, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) downgraded its forecasts for productivity growth. This, in turn, has resulted in the outlook for Government revenue being revised downwards.

Tax expenditures cost £135bn per year. Tax expenditures are tax discounts or exemptions that “further the policy aims of government”. The total sum of all forgone revenue from tax expenditures across income tax, National Insurance contributions, VAT, corporation tax, excise duties, capital gains tax and inheritance tax was £135bn in 2015/16. This is equal to a quarter of the total central government tax revenue in that year, and is larger than the total budgets of all but two departments (Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health).

For capital gains tax, the cost of tax expenditures was more than four times the amount of revenue collected.

This certainly provides a strong indication of the government’s policy and budget priorities, making a mockery of trite sloganised claims of “a country that works for everyone”. Some social groups clearly raise rather more hidden political costs than others, but it is only disadvantaged and marginalised groups that tend to be negatively ideologically portrayed as a “burden” on the state by Conservatives and the media.

In the 2017 Autumn Budget, the Chancellor announced new stamp duty reliefs for first time buyers purchasing properties worth under £500,000. Due to the policy being specifically targeted at first time buyers, this policy resembles a tax expenditure, and in 2018/19 (its first full year) is expected to cost £560m.

Furthermore, the National Audit Office has reported that the Treasury does not monitor tax expenditures and assess the value for money they offer with the same rigour as it does general expenditure. The Institute for Government, along with the Chartered Institute of Taxation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, has called for the tax reliefs that most closely resemble spending measures to be treated as spending for accountability and scrutiny purposes.

Net government liabilities are now over £2 trillion. The Whitehall Monitor report says: “The Government’s net liability has implications for future generations of taxpayers, who will bear the costs of meeting these obligations, but the long-term nature of such obligations can make discussions around the government balance sheet seem more remote than the immediate choices about how much departments should spend each year.

“Nonetheless, policy choices have important implications for the Government’s liabilities – for example, the decisions taken by the Coalition Government to increase the state pension age, and to set a triple lock that guarantees annual increases of at least 2.5% in the state pension, are likely to have contrasting effects on the size of the state pension liability.”

The report goes on to say: “But the Government has made commitments to voters on public services, productivity, social mobility and major projects. If it fails to meet their expectations, it risks further undermining confidence in government.”

The government is still not transparent about its spending plans. The report says that “Better data is needed to understand the benefits – and risks – of outsourced public services”.

“Wider government contracting includes back-office outsourcing by departments and the purchase of goods they use in the delivery of public services (e.g. paper, energy), as well as privately run public services. In 2015/16, £192bn was spent by government on goods and services, of which £70bn was spent by local government, £65bn by the NHS and £9bn by public corporations, with central government departments and other public bodies accounting for the remaining £49bn.

“While some contract data is published, the Institute for Government and Spend Network have previously highlighted gaps in transparency – including on contractual terms, performance and the supply chains of third-party service providers.

“The Information Commissioner has said that the public should have the same right to know about public services whether the service is provided directly by government or by an outsourced provider”. [My emphasis]

The IFG also say in their report: “In 2016, the Public Accounts Committee concluded that the outsourcing of health disability assessments at DWP had resulted in claimants ‘not receiving an acceptable level of service from contractors’, while costs per assessment had increased significantly. [My emphasis. Some 10% of the budget for the Department for Work and Pensions goes to private contractors.]

“Similarly, in 2013 MoJ [Ministry of Justice] found that it had been overbilled in relation to contracts worth £722m.”

There have been numerous high-profile failings in government outsourcing. The recent collapse of Carillion highlights many of the longstanding and existing issues, and should encourage a political focus on solving them.

The report continues: “There is no centrally collected data outlining the scope, cost and quality of contracted public services across government. Nonetheless, we know that Whitehall departments account for only a portion of outsourced service delivery, which can also happen further downstream after departments have provided funds to public bodies (for example, the purchasing of services from GPs by the NHS) or local authorities.”

The next section of the report outlines the 2016–17 parliamentary session, in which 24 government bills were passed – fewer than in any session under the 2010–15 Coalition Government. In part, this reflects the curtailed session, which ended with the dissolution of Parliament on 3 May ahead of the election in early June. The report goes on to say that 1,097 pages of legislation – 38% of all pages passed in the session – were dealt with at speed, raising questions about the adequacy of the scrutiny these bills received.

There were also concerns raised about the scope of the powers the government has sought regarding the EU Withdrawal Bill, which has proven controversial. In particular, the inclusion of so-called ‘Henry VIII’ powers, allowing the Government to amend or repeal existing primary legislation without the scrutiny normally afforded to bills. This has quite properly provoked concern among parliamentarians.

Curiously, the report says that the use of statutory instruments (SIs) – previously used only to pass non-controversial policies and amendments – has dropped. However, this flies in the face of existing evidence, which is sourced from the government’s own site. If there has been a drop since 2014, it certainly contradicts the trend set since 2010. Furthermore, the Government has been criticised for using SIs to pass controversial policies, such as welfare cuts.

It seems that IFG counted the number of SIs by parliamentary session (the parliamentary year which tends to run from Spring to Spring) rather than by calendar year.

Scrutiny of SIs is rather less intensive than scrutiny of primary legislation. They are subject to two main procedures, neither of which allows Parliament to make any amendments:

- negative procedure, in which an SI is laid before Parliament and incorporated into law unless either House objects within 40 days

- affirmative procedure, in which both Houses must approve a draft SI when it is laid before them.

It’s also worth reading: Conservative Government accused of ‘waging war’ on Parliament by forcing through key law changes without debate.

The lack of progress on inclusion and diversity

The IFG says there has been “little recent progress” in numbers of senior civil servants with disabilities or ethnic minority backgrounds, while the percentage of women also decreases proportionally with ascending Whitehall pay scales. .

They report: “The civil service needs to fulfil the promise of its diversity and inclusion strategy, especially in improving the representation of ethnic minority and disabled staff at senior levels.”

Of those appointed to the highest departmental rank of permanent secretary in 2017, “as many were men with the surname Rycroft as were women – two in each case”. The report notes also “there has never been a female cabinet secretary for the UK”.

Despite the much-trumpeted launch of the Disability Confident employment scheme, aimed at “helping to positively change attitudes, behaviours and cultures,” and “making the most of the talents that disabled people can bring to the workplace”, sadly there is no evidence that the Government intends role-modeling positive behaviours or putting into practice what it preaches.

The representation of disabled civil servants at senior level has improved only very slightly: 5.3%, up from 4.7% in 2016. Across the UK population as a whole, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), 21% of people are estimated to have a disability (some 18% of the working-age population).

Lack of openness, transparency and accountability

In the UK, the idea that government should be open to public scrutiny and policies congruent with public opinion is central to our notion of democracy. Government openness and transparency also tends to be linked with citizen inclusion, democratic participation and a higher degree of collaboration between citizens and government on public policy decisions. It also ensures that corruption and the misuse of political t power for other purposes, such as forms repression of political opponents is less likely.

Information and data deficits are more likely to lead to political corruption and a reduction in democratic accountability.

The IFG report says that in 2016–17, more ministerial correspondence was answered in time, which were thanks to more generous targets, while fewer parliamentary questions were answered on time and information was withheld in response to more Freedom of Information requests.

Parliament has other mechanisms to hold government to account, including urgent questions (which have most tellingly increased significantly in recent years) or select committee inquiries (which have also increased in number, with the election delaying government responses). The Government has established a track record of withholding details of planned legislation from the opposition. (See for example: PIP and the Tory Monologue).

According to Democracy Audit UK – an independent research organisation, established as a not-for-profit company, and based at the Public Policy Group in the LSE’s Government Department – the lack of transparency has been fuelled by the coalition period, and now, the Conservative’s’ narrow majority, as the amount of secondary legislation is growing, and primary legislation is drafted in ways that increasingly leave its consequences obscure, to be filled in later via statutory instruments or regulation. Commons scrutiny of such “delegated legislation” is subsequently reduced, and likely to be very weak and ineffective.

Meanwhile, departments’ publication of mandated data releases, including spending over £25,000, organograms and ministerial hospitality, is patchy. Departments also proactively publish on GOV.UK, though supply and demand differs by department

The IFG says that many departments are not publishing their data as frequently as they should and this, coupled with the difficulty of measuring government performance, suggests that the government is becoming less transparent and accountable.

A rise in the numbers of Freedom of Information requests that are being refused

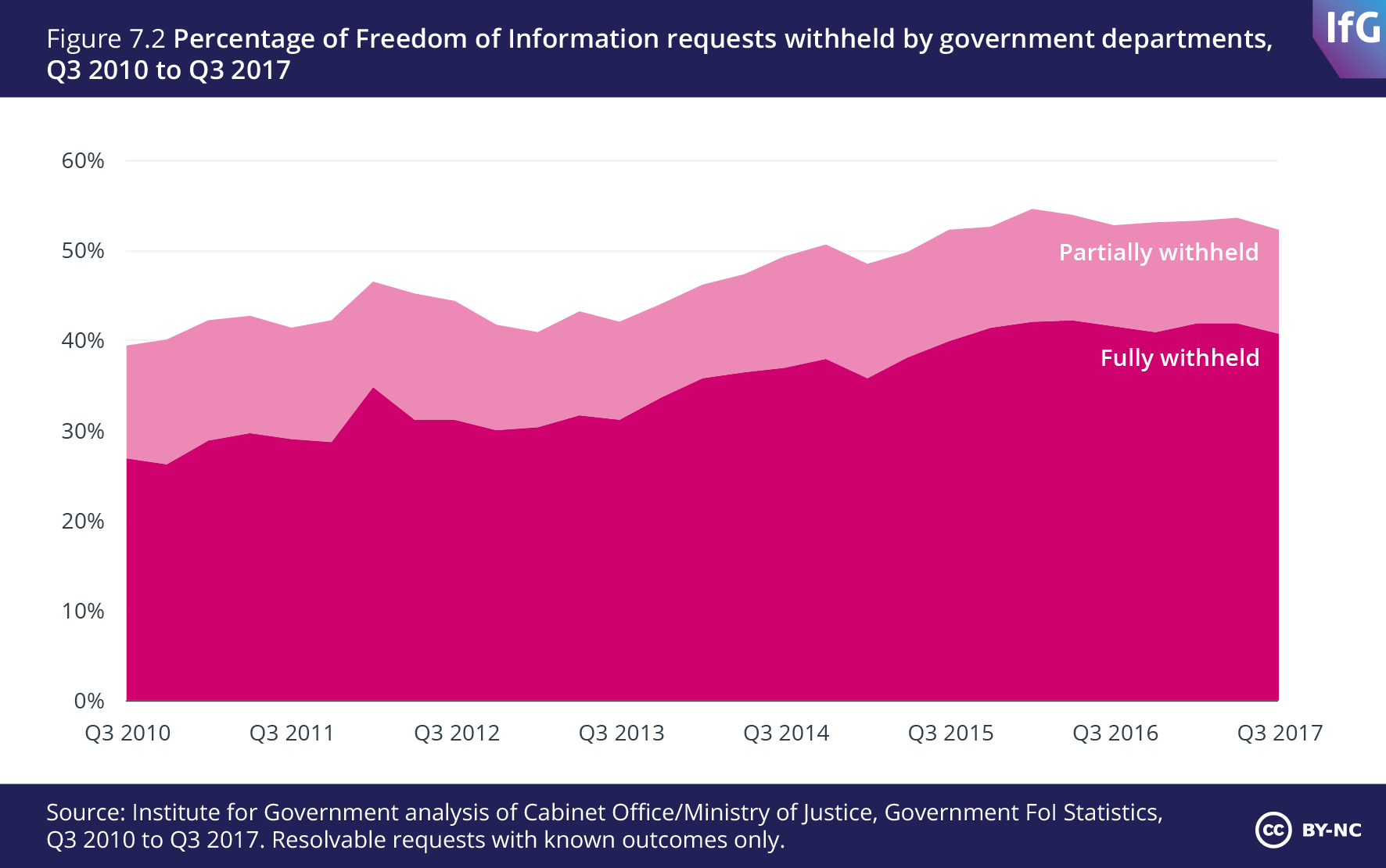

Since 2010, government departments have become rather less open in response to Freedom of Information (FoI) requests. In 2010, 39% of requests were fully or partially withheld; this had increased to 52% by 2017.

Departments are able to refuse requests on a number of grounds: if the request falls under one of the 23 exemptions in the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (such as national security or personal information) or those in the Environmental Information Regulations; if it breaches the limit for the cost involved in responding (£600 for central departments and Parliament); if the request is repeated; or if the request is ‘vexatious’ (meaning it is likely ‘to cause a disproportionate or unjustifiable level of distress, disruption or irritation’).

Of the 2,342 requests withheld in full in 2017, 50% were held to be due to FoI Act exemptions, 47% to cost, 2% to repetition and 1% to vexatiousness.

Of course exemptions may also be used as “good reasons” – excuses – to withhold inconveniently controversial information that is likely to bring valid criticism and cause scandal.

Mike Sivier‘s request for information about how many people have died after going through the Work Capability Assessment, which had resulted in a decision that they were fit for work, was originally refused. The figures were only released after the Information Commission overruled a Government decision to block the statistics being made public, through Mike’s Freedom of Information request.

After the request, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), an independent authority set up to uphold public information rights, agreed that there was no reason not to publish the figures, despite the Department for Work and Pensions variously claiming the request was “vexatious”, and that it “could impose a burden in terms of time and resources, distracting the DWP from its main functions”.

However, clearly the real reason for the original refusal of this request is that the information was highly controversial and contradicted political claims regarding the completely unacceptable level of harm that has been caused to citizens by the damaging impact of the Conservative’s draconian welfare policies.

The ICO said: “Given the passage of time and level of interest in the information, it is difficult to understand how the DWP could reasonably withhold the requested information.”

More recently, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has continued to try to block John Slater’s FoI request which is likely to expose the widespread failings of two of its Personal Independent Payment (PIP) disability assessment contractors, initially claiming that it did not hold the information he had requested, before arguing that releasing the monthly reports would prejudice the “commercial interests” of Atos and Capita.

The DWP later told the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) that releasing the information “will give rise to items being taken out of context… [and] will be misinterpreted in ways that could lead to reputational damage to both the Department and the PIP Providers”, and would “prejudice the efficient conduct of public affairs” by DWP.

It also warned the ICO that the information could be “maliciously misinterpreted to feed the narrative that the Department imposes ‘targets’ for the outcomes of assessments”.

However, that comment alone indicates the highly controversial nature of the information being withheld, and thus also betrays the real motive. Information is being restricted to stifle legitimate criticism of Government policy and to hide from public view the empirical evidence of its consequences.

The ICO has nonetheless ordered the release of the information requested. A DWP spokeswoman said: “We have received the ICO judgement and we are currently considering our position.”

If the DWP disagree with the decision and wish to appeal, it must lodge an appeal with the First Tier Tribunal (Information Rights) within 28 calendar days. The requester also has a right of appeal.

The ICO say: Failure to comply with a decision notice is contempt of court, punishable by a fine.

It’s also worth noting that the DWP are obliged to inform any contractors of how the Freedom of Information Act may affect them, making it clear that no guarantee of complete confidentiality of information may be made and that, as a public body, it must consider for release any information it holds if it is requested.

The Department for Exiting the European Union (DExEU) overtakes the DWP to become the most opaque department. This is one example of a wider lack of transparency around Brexit and reflects the wider reluctance of the Government to share assessments of the anticipated impact of Brexit on different parts of the UK economy. Publication of spending and organisational data remains patchy, suggesting departments are not using the data themselves.

The Scotland Office, Wales Office and Department for Transport tend to grant more requests in full, and in a timely manner. Among the more opaque are several departments regularly granting fewer than 30% of requests, particularly since 2015, including the Cabinet Office, Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), the Treasury, HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and Minstry of Justice (MoJ).

None of the departments created in July 2016 – DExEU, DIT and BEIS – has ever granted even half of its total requests in full. In the three-quarters leading up to Q3 2017, DExEU was the least likely of all departments to comply with FoI requests, respectively answering 18%, 10% and 15% in full. It also refused a higher percentage because they were considered “vexatious” than any other department in 2017; 14% of requests.

The IFG report says “DExEU’s lack of transparency here, and its tardy responses to other requests for information (though not on FoI, where it is the sixth most responsive department), are consistent with its wider reluctance to release information, including the Government’s assessments of the anticipated impact of Brexit on different parts of the UK economy.”

You can read the full IFG Whitehall Monitor Report here

I don’t make any money from my work. But you can support Politics and Insights and contribute by making a donation which will help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated, and helps to keep my articles free and accessible to all – thank you.

Reblogged this on World4Justice : NOW! Lobby Forum..

LikeLike